Discover latest facts & figures on the development of gender diversity in the Swiss workplace. Benefit from deep insights into current challenges and their causes combined with hands-on recommendations.

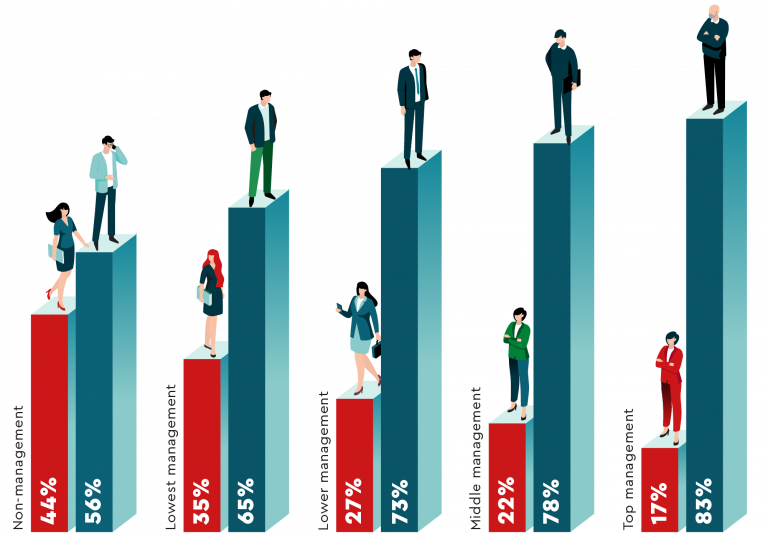

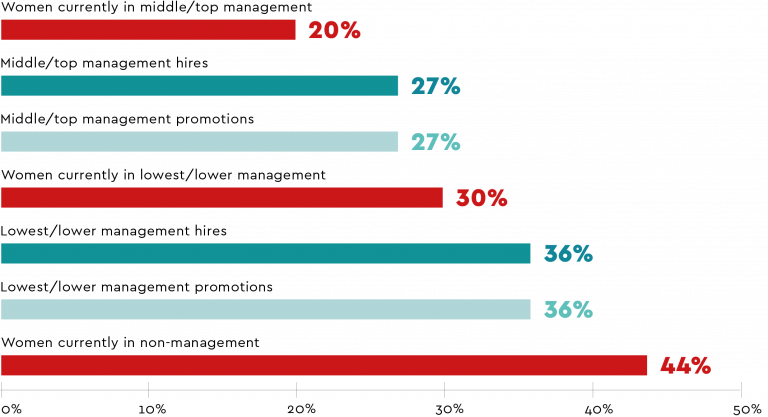

Companies often lament that there are simply not enough qualified, diverse talents in the labor market. But with 44% women in non-management, companies already have the diverse talents they need in-house. The problem is that women remain underrepresented in upper management, at only 17% in top management.2 The “leaky pipeline”, where women are (nearly) equally represented in non-management yet barely represented in top management positions, has been a fixture in the Gender Intelligence Report every year. The female talent pool represents a unique potential that remains underutilized, both to diversify management and confront the increasing skilled labor shortage (Sander & Niedermann, 2021).

2 This year’s sample of participating companies has rather a high proportion of companies from the MEM industry, which have particularly low female representation across all hierarchical levels. This is why this year’s numbers appear lower than in previous iterations of the Gender Intelligence Report.

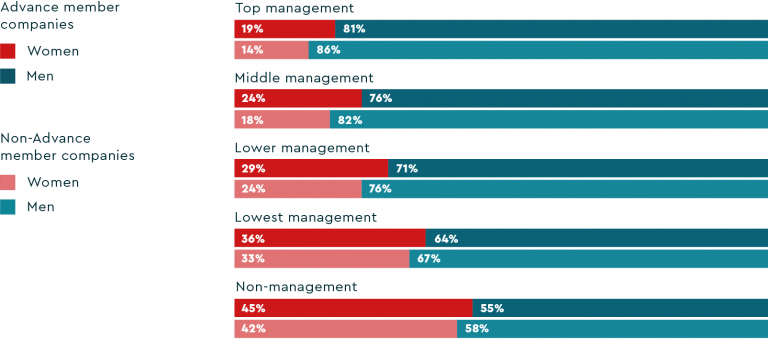

Advance members do better than non-Advance members regarding the share of women at each management level. In top management, women at Advance member companies have a representation five percentage points higher than at non-Advance members. Yet, the pattern is the same, and the share of women decreases at each management level.

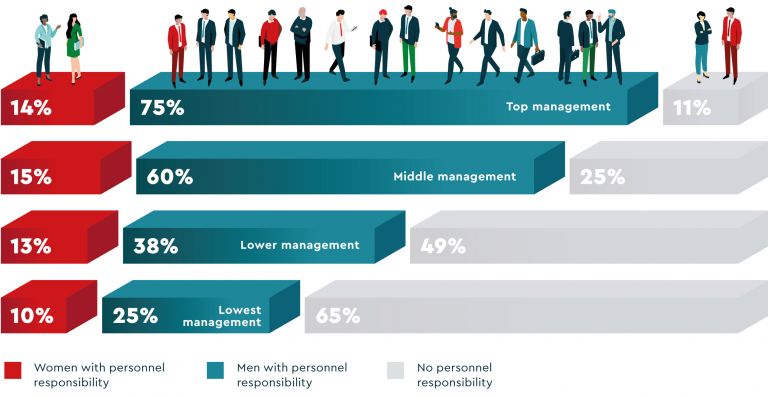

At first glance, a representation of 35% in lowest management and almost 30% in lower management may seem quite significant. This significance is because, at a representation of about 33%, members of the minority group may influence the organizational culture (Bohnet, 2016; Kanter-Moss, 1977). However, how much power do women actually wield?

When looking at positions of personnel responsibility, it becomes clear that men hold more influence and decision-making power at every management level. In lowest management, where women are represented at 35%, there are very few positions with personnel responsibility. Considering the overall sample, women’s share of positions with personnel responsibility remains between 10% and 15% on the various management levels, whereas men’s share increases consistently with each higher level.

This pattern shows compellingly that the power gap increases with each management level. While the share of men with personnel responsibility increases at every level, the share of women stays practically the same.

In other words, many women in lower management positions are not in the “springboard positions” with the visibility likely to catapult women to the top. Taking on personnel responsibility can make someone stand out when it comes to promotions, making employees with personnel responsibility in lowest management more likely to make it higher. Women in low management may be stuck in “nominal” positions (expert or admin roles without personnel responsibility), where they have little chance to advance down the line.

Spotlight

For almost two years now, a law has been in effect in Switzerland that imposes gender quotas on the e-boards and boards of directors of listed companies. Companies that fall short of the set standards will soon have to explain publicly why they are not complying with them and announce measures to remedy the situation.

It seems self-evident that measures must also be effective, because “a measure is an action with the intention of achieving a certain goal.” But this definition – and one can also replace the term “intention” by “purpose” – leaves the question of effectiveness or its verification open.

Our legal system recognizes the principle of proportionality. The law can therefore only require companies to take measures that enable them to achieve their goals at a reasonable cost. This is certainly reasonable in order to maintain focus. But in order to assess proportionality, one must know about effectiveness, i.e. know about what is happening exactly. But how?

A “measure” is not only an undertaking, but it can also mean “assessment”. Annual studies such as this very “Gender Intelligence Report” by Advance and the Competence Centre for Diversity & Inclusion at the University of St. Gallen and the “Diversity Report Switzerland” by GetDiversity provide an important basis for determining and verifying the effectiveness of measures.

If you see year after year that Advance member firms achieve better results in terms of diversity than the non-member peer group, then the priority that member companies give to the issue of diversity, as well as the money and time they spend on it, are arguably effective.

If we see year after year that companies that have to adhere to quotas in laws and ratings from institutional investors have a much better mix of diverse people in their boardrooms than those that do not, then quotas are probably effective.

Still: 35% of all listed companies in Switzerland still have ZERO women on their boards of directors and 58% do not have any women at all on their executive boards. Only 19% have already achieved the gender benchmark on the board of directors – 26% on the executive boards. Only 6% achieve the legally required mix in both the board of directors and the executive management. There is still a long way to go.

Companies that systematically diversify their talent pipeline and develop their culture of collaboration toward inclusion so that diversity can take effect at all levels within the company already have an advantage in the tight labor market. Finding and retaining good specialists and managers is becoming a strategic advantage for companies. Those who systematically invest in diversity and the culture of inclusion today will be rewarded with compound interest in the labor market and in company value.

CEO GetDiversity

If we keep progressing at the current pace, the share of women in management will only increase by five percentage points, from 27% to 32%, by 2030. That increase is still far away from equal representation.

If all industries were to hire and promote at the same rates as the MEM industry, which uses its small talent pipeline exceptionally well, we would reach 41% women in overall management by 2030 (up from 27% in 2021). And full parity could be reached within 20 years, around 2042! However, if we continue at the current pace, it will take another 100 years until we get there.

This slow expected growth reinforces the conclusion that “more of the same” is not enough to affect meaningful change. So what is the hang-up?

Swiss companies don’t have a “pipeline problem.” In fact, companies in Switzerland often already have myriad female talents in-house. After all, 44% of non-management employees are women, as are 35% of employees at the lowest management level.

Demographic trends also point in the right direction. According to the latest analysis by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (2022), the labor force participation rate in Switzerland has increased by 1.6 percentage points over the past ten years. Although the rate for men is still higher than that for women (87.5% vs. 79.7%), the difference between the sexes has narrowed (from 11.5 percentage points to 7.8 percentage points). This narrowing means that increasingly more women are participating in the labor market, increasing the potential female talent pool significantly.

A minor, positive development can also be observed with regards to part-time employment of men. While part-time work remains widespread among women (57.5% of employed women aged 15-64 in 2021), the share among men increased by 3.8 percentage points between 2011 and 2021 to 15.5%. Suppose the part-time rate of men continues to rise, and women and men are employed part-time or full-time at similar rates. In that case, traditional gender norms (e.g., mothers working part-time) may change in the direction of a more partnership-based task division of gainful employment, household, and family work, further evening the playing field for diverse young talents in the future. This scenario would leave fewer excuses for companies as to why they don’t have more gender-diverse management ranks.

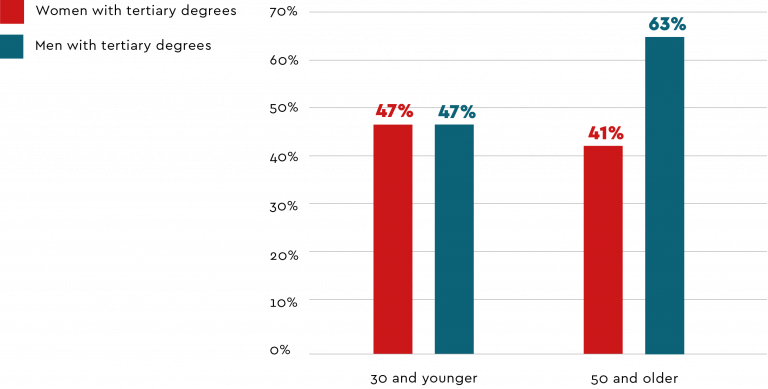

Moreover, young female and male employees currently have practically identical educational backgrounds. In previous generations, male employees were significantly higher educated and had significantly better chances of advancement. Today, men and women under 30 are equally well educated regarding tertiary degrees (though for men, the share of non-management employees with university degrees is minimally greater). This educational similarity also holds for non-management.

Graduation rates over the last few years paint a hopeful picture regarding future diverse pipeline potential. According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, the proportion of people with tertiary-level qualifications (higher vocational training and university degrees) in the population aged 25 to 64 is expected to rise from 44% in 2019 to 51% in 2030. Migration trends bolster this development: 60% of immigrants have a tertiary degree (FSO, 2020).

Female graduates are leading the charge. Including universities of applied sciences, 53% of all university degrees went to women in 2020.3 However, women and girls still lag men and boys in some subjects. In business-related fields, only 35% of university bachelor’s and master’s degrees go to women. However, in universities of applied sciences, most bachelor’s degrees in the same field go to women. For example, 39% of university degrees in exact and natural sciences go to women. In technical sciences, the share of women is again lower – 35% of bachelor’s degrees and 32% of master’s degrees, though it should be noted that this number was seven percentage points lower ten years ago (FSO, 2022).

3 The last year for which this statistic was made available.

The gender drift between “girl” and “boy” subjects starts early. In childhood, boys’ and girls’ interests in math and sciences are encouraged differently so that they enter primary school with different levels of subject knowledge (Solga & Pfahl, 2009). Boys’ and girls’ interests in school diverge around grade 7, where boys move towards maths and sciences, and girls towards languages and art (Brovelli, 2017). For instance, women only comprise 9% of successfully completed apprenticeships in software and application development and analysis (FSO, 2022).

But this difference in subjects should not serve as an excuse for companies. For one, they can take the initiative and try to influence the diversity of their pipeline early. For instance, companies might start or support educational programs or initiatives designed to inspire high school students, especially girls, to consider a future in STEM. Research shows that lack of relatable role models and early understanding on what a career in tech actually entails, are crucial factors that keep girls out of STEM – and these are gaps that companies can help bridge (Ostrowski, 2017). A company who is attracting and recruiting women for tech roles is Accenture, who, with their Cloud Infrastructure Engineering Female Voices initiative both showcase their female talent as speakers at conferences and in so doing create role models to attract more women to engineering and Accenture. It’s a virtuous circle. For inspiration click here.

Companies can also support higher vocational training for their diverse employees, which bolsters their chances of advancement. Higher vocational training often has a strong connection to the profession practiced and is therefore usually completed closely with the company where the trainees are employed. One-third to two-thirds of trainees are in a management position just one year after completing higher vocational training. This proportion increases by four years after graduation (FSO, 2022).

The pipeline is bursting with (diverse) potential. But unless it is properly managed, the face of leadership will remain predominantly male (and white). Middle and top managers are a homogeneous group; 80% are male. Of these men, 70% are Swiss, 74% German-speaking, over 60% have tertiary degrees, and 45% are over 50. Looking at just top management, well over 55% are over 50 and over 8% over 60. As long as this group remains the same, real cultural change remains unlikely, as these employees were likely socialized, educated, and brought up similarly.

While companies are increasing the share of women in management through promotions and new hires, there is little evidence overall that they are fully utilizing their diverse talent pipeline. If we consider non-management employees as the potential talent pool for lowest and lower management, then internal development efforts (promotions) are not fully utilizing this pool. While women make up 44% of non-management, only 36% of lowest and lower management promotions are women. Looking at the middle and top management promotions, it’s a bit better. From the lowest and lower management “pool” (30%), there is a 27% female share of middle and top management promotions, showing that the talent pool is relatively well utilized (though women remain underrepresented).

The numbers for recruitment are identical, indicating that the external talent pipeline also remains underutilized.

Yet Swiss companies and organizations are finding themselves with a unique opportunity. In middle and top management, many men from the baby boomer generation will retire in the coming years. This wave of retirement provides an opportunity to think about what the top management of the future will look like in terms of diversity, skills, (inclusive) mindsets, values, etc. These retirements are also an economic challenge. At the end of 2021, the Swiss Skills Shortage Index for highly skilled professionals increased by 27%, compared with the summer half-year of 2020 (Adecco, 2021). These retirements also pose a key challenge due to the loss of knowledge. This challenge must be considered when focusing on sustainable talent management.

Due to the impending shortage, employers are dependent upon reaching talents from all backgrounds and developing and retaining the promising talents they have. This search for new employees means rethinking who should be considered a talent. Traditional conceptions of “talent” tie the term to a particular age group or education level (Ritz & Sinelli, 2011). This connotation often goes hand in hand with the idea that being considered a “talent” is an exclusive designation for select employees who should be identified as early as possible, nurtured, and all efforts made to retain them (von Hehn, 2016). In contrast, inclusive talent management assumes that “talent” is seen as something every employee has in some form and can represent – in different ways and for different pathways – potential.

Spotlight

Organizations’ lack of progress on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is often attributed to “unconscious bias” or “pipeline problems”. These DEI buzzwords have gained traction over the last decades, likely because they’re easily addressed with a quick training and they place the onus of solving the problem elsewhere. But, as we’ve seen in recent years—even in the 2021 Gender Intelligence Report’s (GIR’s) sadly stagnant share of women in leadership—this isn’t enough. And perhaps more importantly: this isn’t sustainable.

“Grand challenges like climate change are knocking at our door, but to accelerate progress here, too, we need to make the most of our trained (female) talents’ input, creativity, and innovation.”

Indeed, women might be more affected by climate change and related phenomena, but women might also be uniquely positioned to proactively address the climate and related crises. For example, on average, women have smaller carbon footprints than men, more-responsible attitudes towards climate change, and greater interest in protecting the environment. So, paired with their more compassionate, collaborative, and communicative leadership, female leaders may be well-positioned to lead effectively in such crises.

To do so will require bold leadership, accurate evidence, and a dash of humility to find and fix the problematic people, practices, and even “myths” that mire organizations in the past, perpetuate inequalities, and constrain our future. For example, women should be able to pursue diversity and sustainability strategies and initiatives without backlash – but of course these issues are so critical and pressing, requiring men’s care, concern, and involvement as well. But evidence is needed to facilitate effectiveness in these areas, and we often lack even basic data. Thus, we need coordinated, data-informed efforts from leaders and employees, finance, D&I, and sustainability teams, because input from various stakeholders is the best recipe for long-term progress and success.

With your motivation and partnership, paired with the consistent, close monitoring of the annual GIR, we at the CCDI and at Advance, can make measurable and meaningful progress together. After all, it’s about time for leaders to step up their sincere, evidence-informed DEI efforts before we’re all out of time.

Assistant Professor

Read more:

We Can’t Fight Climate Change Without Fighting for Gender Equity

What to Do About Employees Who Consciously Exclude Women

Diversity dos and don’ts: Gender equality by design

One way it becomes evident that Swiss organizations have a non-inclusive leadership culture is by looking at employment percentages. The higher the management level, the higher the employment percentage, irrespective of gender. To be a leader, working full-time is still the norm. Yet men work at higher employment percentages (full-time or near full-time) at all hierarchical levels, while women are much more likely to work part-time. Therefore, to achieve a higher level, women must increase their employment rate, which can be challenging due to timing. It is right around “family primetime” that women decrease their employment percentages – which coincides with the age group where most promotions happen, between ages 31 and 40.

What does this mean? Companies in Switzerland seem “stuck” on a preconceived notion of what a leader – and what leadership – looks like. This image is based on a family model where the man is the primary breadwinner for his family and has a wife/partner at home who supports him with home/family care (Aboim, 2010; Ciccia & Verloo, 2012). If career trajectories and expectations are rigidly tied to this traditional image, diverse employees are not the only ones who lose out on a seat at the table. With the skills shortage becoming an urgent reality, Swiss organizations also lose out on an invaluable, diverse talent pool simply because they are unable to rethink the image of a leader.

Spotlight

What’s the difference between female and male “money biographies”? The “money life” of a man is sketched quickly: One straight line, pointing up. The typical man steadily accumulates more money in his life, increasing what he makes and invests.

A woman’s financial life, on the other hand, resembles a tangled curve with some ups, but mostly downs. It is marked by interruptions, gaps, phases without money full of part-time work or unpaid care work for children, parents or dependents. The financial life of the average woman is at a lower level early on and never swings back up to the heights of a man’s, ending up in a “pension gap” of 37 percent.

The money “gaps” in women’s lives start with pocket money, continue through wages and investments, among other things, and end with lower retirement benefits. The gaps are numerous and reinforce each other throughout women’s lives. With which result? 56 percent of women in Switzerland cannot keep one’s head above water financially, and this in the second richest country in the world. This hinders independence and leads to dependency on men – making money the last front line in terms of equality.

“Women know a lot more about money than they think and should take financial matters into their own hands.”

Both the tax and social security systems in Switzerland contribute significantly to these money gaps. The problems are well known: For example, an initiative for individual taxation is underway. On the other hand, the abolition of the coordination deduction, which deprives part-time workers and poorly paid women of their pension money, was defeated despite 35 years of fight. The parental leave initiative was also rejected. Parliament is still male dominated. Political system change takes time – time that women do not have. That’s why knowledge and education about the gaps – and how to close them in your own life – are enormously important.

Women know a lot more about money than they think and should take financial matters into their own hands. Waiting for the system to change is not going to help anyone. Only those who know the money gaps can close them or, better yet, avoid them. “Know the gaps, mind the gaps, and close the gaps!”

Economist, award-winning journalist and CEO elleXX Universe AG

The pandemic provides a unique opportunity to reimagine leaders as individuals with unique needs and wants. This opportunity came because most companies now have significant hands-on experience with flexible working. Flexible work, when done right, is also a unique opportunity to demonstrate trust and empower employees (Hussain et al., 2014).

A company focused on not only what their definition of leadership is but also the lived behavior of their leaders is EY. They are using storytelling to engage leaders and create a psychologically safe work environment, coupled with active listening techniques so that their diverse employees are feeling heard and better understood. For inspiration click here.

Inclusion – and an inclusive organizational culture – is a key factor in building a sustainable and diverse talent pipeline. However, inclusion goes beyond only attracting, developing, and retaining employees so they have the competencies and commitment to ensure the organization’s success (Pasmore, 2015). Instead, inclusion necessitates building a culture where diverse talents with unique needs feel valued, are heard, and have a sense of belonging. Sustainable talent management is about empowering diverse talents so that they can actively shape the inclusive (leadership) culture they need to thrive in the long term. This empowerment ensures that an organizational culture where diverse talents can thrive becomes a long-term reality. Thus, inclusion is an essential prerequisite for sustainable talent management.

Last year, we asked Swiss companies to manage inclusion like a business. This year, we want to know, what are Swiss organizations actually doing to build inclusive cultures and foster inclusive leadership?

A company managing to integrate inclusion into their overall SIX Spirit transformation strategy is SIX. An internal trainer community created across hierarchy levels is working to take every employee on a shared journey towards an open, inclusive and growth-oriented culture. For inspiration click here.

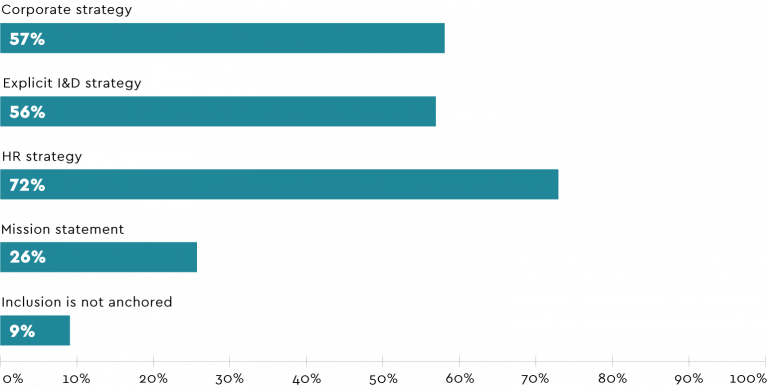

Are most Swiss organizations currently prioritizing inclusion? The short answer – it depends. The majority (above 50%) feature inclusion as part of their HR strategy, I&D strategy, corporate strategy, or all of the above. However, including “inclusion” in the HR strategy seems significantly more prevalent than inclusion as part of the corporate strategy or mission statement (though not all companies possess the latter), which signals that inclusion is perceived as an HR issue, not a topic central to its core business. Incorporating inclusion in its mission statement demonstrates that a company considers it a part of its core purpose. If inclusion is a key value for the company, it should be reflected in the core.

In contrast to inclusion, 66% of companies include “diversity” in their corporate strategy, and 32% include it in their mission statement. This difference in strategy and statement signals a stronger understanding that diversity is key for business success. However, the awareness that diversity cannot thrive without inclusion has not been fully established throughout the Swiss business consciousness.

61% of companies have measurable, overall inclusion goals. While this number may seem high, it is still lower than those companies with measurable diversity goals (72%). This difference matters because companies who focus on diversity goals without the combination of inclusion goals may promote assimilation into the old organizational culture. Assimilation contrasts with the positive cultural transformation that comes from inclusive employees (Jacobs et al., 2022).

Inclusive leaders are the people who build inclusive teams and serve as role models in daily business life (Nishii, 2013, Shore et al., 2011). These leaders manage inclusivity to work towards the company’s shared vision for the inclusive culture they plan to establish, thus getting the organization to achieve its goals (Korkmaz et al., 2022). Inclusion goals for managers may include proven conflict resolution skills, participation in inclusion trainings (e.g., psychological safety or inclusive leadership), team-level engagement survey results related to inclusion, etc. Leaders need to be held accountable for achieving these goals. Managers should not be surprised when it comes time for performance reviews on whether they successfully fostered inclusion. Yet only 36% of companies have measurable inclusion goals for managers, compared to 49% of companies with diversity goals. Is it truly realistic to achieve diversity goals if those goals are not linked to inclusion?

While inclusion goals need to be improved, it is important to note that more companies are providing leaders with the key tools to foster inclusion. 57% of companies make inclusive leadership an integral part of leadership development programs, and 52% do the same for psychological safety. A company living up to its inclusion goals through manager training and linking it to promotion chances is PwC. Their Inclusive Mindset Learning Pathway is a comprehensive self-paced learning journey which spells out for managers the benefits and the ‘how to dos’ of inclusive leadership. For inspiration click here.

Ultimately, being an inclusive leader is about respecting another human being. Respect, and the reciprocation of such, takes inclusive leaders beyond the normal business case for diversity (Wettstein, 2012). This type of treatment of employees bridges the business case to the business and human rights perspective and humanistic management view (Pirson, 2017). These views create a holistic portrait of an employee. They are more than just a worker; they are a person who deserves a life of dignity, a maximization of their freedoms, and the psychological safety to work unhindered. But for this to matter, leaders need to be held accountable.

A company which takes an innovative approach to setting targets by empowering divisions to set their own, is Swisscom. For inspiration click here.

Organizational key performance indicators (KPIs) should not only be put on behaviors but also key HR decisions. These decisions may include recruitment, talent development, retention, performance reviews, and promotions.

Hiring for inclusion is a key step in sustainable talent management, creating the pathway to sustain and strengthen an environment that empowers and values diverse talents. This can be done through hiring for inclusive cultural fit. Many organizations fall into an exclusionary trap when looking to hire specifically for “cultural fit” (i.e., looking for potential employees who are most similar to the current company climate). To mitigate this trap, it is key to recruit candidates for whom inclusion is truly a core value.

Interestingly, companies seem more focused on inclusive behaviors when it comes to promotions than hiring. This focus may be because it is easier to judge inclusion skills with employees who have already proven these skills in practice. That companies are not seeing the interconnection between diversity and inclusion is apparent when considering the inclusion of diversity goals in key HR processes – 88% have diversity goals for recruitment, 64% for promotions.

To manage and foster an inclusive culture in your organization, involve leaders and employees from all organizational levels. This collaboration allows for authenticity when implementing inclusion where employees feel valued, that they have a voice, and that they belong. A collaborative effort starts with creating safe spaces as communities for support, connection, exchange, and learning. To help incorporate and better support employees, organizations often institute Employee Resource Groups (ERGs). This implementation of ERGs offers employees a voice, though organizational support is key as not to put undue burden on marginalized employees (click here to read more).

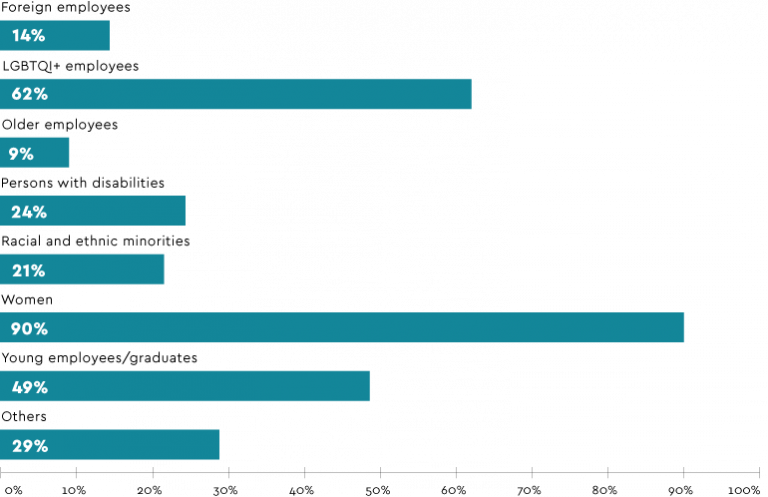

The good news, 90% of organizations have ERGs or D&I networks for women, and 62% have the same for LGBTQI+ employees. However, organizations tend to put considerably less emphasis on programs for groups other than women. Only about 1 in 5 organizations has an ERG for racial and ethnic minorities, for instance. Being more inclusive means accepting that diversity is truly intersectional and making resources available to all potentially stigmatized groups.

Swiss organizations still need to take a more intersectional approach when supporting employees. Why does this matter in a gender report? First coined by American academic Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), intersectionality focuses on how the overlap of one’s identities may create more or less privileges for that person. After all, each woman is more than just their gender, and from an intersectional view may have multiple identities. For example, the intersection of gender and sexual orientation shows that a woman who is White and heterosexual will have more privilege than a woman who is White and homosexual. Both White women, when incorporating the intersection of race, will have more privilege in the workplace in comparison with Black women. Between Black women, there is a difference in privilege regarding sexual orientation as well. Creating systems that include the most marginalized, and those identifying with multiple marginalized groups, is the fastest way to include all, including the dominant majority group – it’s a win-win-win (Praslova, 2022; Shore et al, 2011). Systemic inclusion that considers intersectionalities comprehensively addresses all barriers and embeds inclusion in all talent processes and decision-making mechanisms.

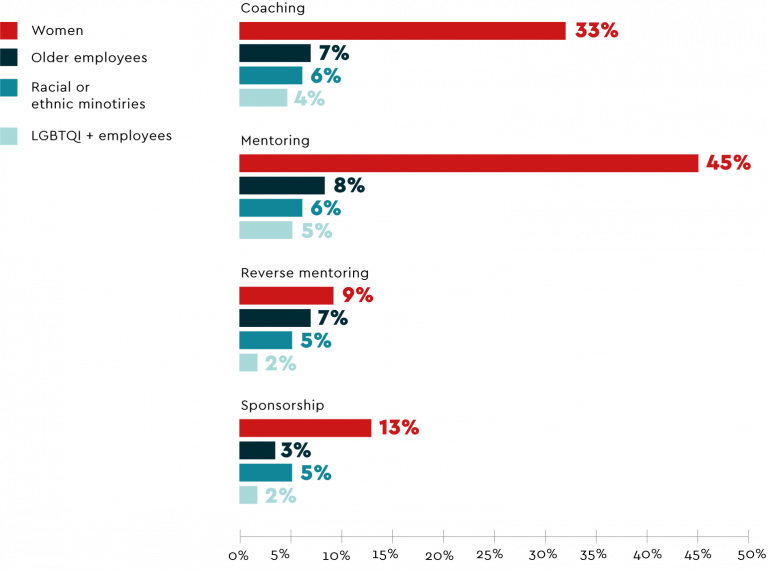

Due to the lack of privilege of employees from marginalized groups, it is important Swiss organizations support them through leadership development and other opportunities. Types of programs that can support these employees may include sponsorship, coaching, reverse mentoring, and mentoring. Here, too, a lack of intersectional mindset becomes apparent. 45% of companies surveyed have mentoring programs for women, which is already less than half (and considerably lower than the number of companies that have ERGs for women, which often wrongly involve less organizational effort to set up). However, initiatives for employees who come from other groups exist in a small percentage of organizations.

Spotlight

Colorism is a form of discrimination that occurs due to people from the same racial group having different skin tones. This type of discrimination is rooted in racism. Those from a racial group who have lighter skin tones are perceived to be more privileged as their looks are more accepting in places that are White controlled. From an intersectional point, colorism is more injurious to women of color than men. In the workplace this is, for example, evident in the bias of management against Black women with natural hair compared to those with straight hair (Koval & Rosette, 2021). Due to increased privilege, lighter skin toned people may treat those who have darker skin tones worse than their White counterparts. There is an incentive for lighter skin toned members of a racial group to adopt styles that make them even more “White passing” in many academic or professional environments. The treatment of Black girls in high school demonstrates the impact of colorism. Hannon, De Fina, and Bruch (2013) showed that among these girls, those who were darker skin toned were three times more likely to be suspended than their light-skinned peers.

“An organization that is anti-colorist nullifies the traditional (White) European ethnocentric standards that cause the marginalization of people of color, and embraces a true intersectional approach to inclusion.”

Understanding colorism is essential for inclusive leaders in Swiss businesses. Leaders need to recognize when they may be complicit in colorism, and create the environment to overcome it. This mitigation of colorism will allow women of color the psychological safety to be themselves without fear of discrimination due to their skin tone or hairstyle.

One last point on the topic of hair – if you are an ally never ask a Black person if you can touch their hair (yes it happens).

For the first time, the GIR includes analyses for individual industries. In what follows, you can find answers to questions such as: Do the above conclusions hold for all industries? Are there some industries that lead the charge when it comes to gender diversity and inclusion, where women advance in their careers at a similar pace to men? Are there industries that lag behind? And where does YOUR industry stand?

Find out how you can champion inclusion at your organization