4 “MEM” industries, as used here, includes not only the machine, electrical, and mechanical engineering companies but also other companies with similar structures and in related fields.

While the number of engineering positions has doubled in the first decades of the 2000s, the number of graduates with technical degrees has not kept pace (Minsch et al., 2017). This means that the MEM industry is dependent upon reaching all available talents. How are companies in the MEM industries managing and feeding their talent pipelines? Are they able to attract and retain diverse talents?

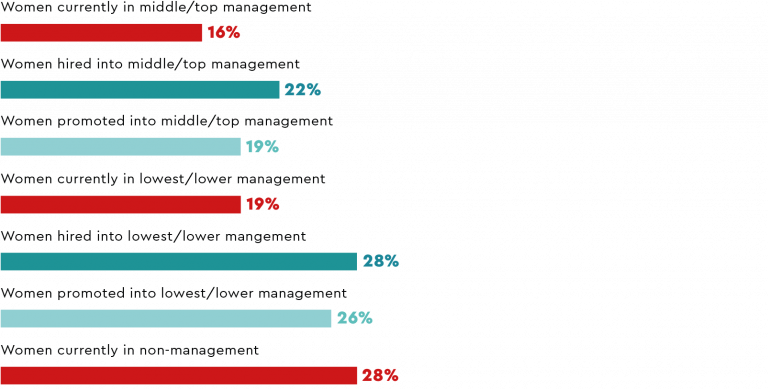

The MEM industry has the lowest share of women of any industry included in this year’s GIR. Only 24% of the overall workforce is female. Furthermore, at 28% of women in non-management, the MEM industry’s female talent pool is considerably lower than is the case for other industries. Yet, the 15% of women who are top managers is only marginally smaller than in almost all other industries. This means that while the share of women is low throughout, companies in the MEM industry do a relatively good job fostering gender diversity in managerial positions.

From an intersectional perspective, an interesting trend emerges in the MEM industry; women are considerably younger than men. 47% of all female managers are aged 40 or younger. For men, it is just 30%, a tendency more pronounced than in the overall sample. 46% of male middle and top managers are over 50 years old, which indicates that a wave of baby boomer retirements in leadership is about to hit the MEM industry. This wave provides an opportunity to fill spots with diverse, inclusive leaders but also brings a danger of significant loss of crucial knowledge and the challenge to find enough leaders to fill open positions. Companies in the MEM industry have an excellent opportunity to proactively manage the knowledge transfer between generations and genders.

While the typical talent is male, Swiss, and between 31 and 40 years old (looking at promotions), the MEM industry is utilizing both promotions and new hires to increase the share of women in springboard as well as middle and top management positions. The MEM industry is also leveraging its potential. The share of women promoted into lowest and lower management, for example, is about equal to the share of women in non-management, which indicates that the MEM industry is making good use of its diverse talent pool. The overall female promotion rate (25%) is also similar to the share of women in MEM companies (24%).

In the MEM industry, women are recruited into management from outside comparatively more often than they are promoted. With this focus, the MEM industry specifically aims to expand the internal female talent pool.

But who are these women newly recruited into MEM companies? The share of foreign women among new management hires is considerably higher than their current share. While 57% of women currently in management positions in the MEM industry are Swiss, the share of Swiss women among new management hires is only 37%. This tendency also exists for non-management hires, though less pronounced. This share is considerably smaller for men, where 54% of new managers are Swiss, compared to 65% of Swiss male managers currently working for MEM companies. This is partly because in Switzerland, the share of women in engineering and technical degrees is lower than is the case abroad, including most of Europe (UNESCO, 2020). Such diverse profiles require careful inclusion strategies to ensure everyone feels valued (and to prevent higher turnover rates of diverse talents). If there are very homogeneous subgroups with little overlap (non-Swiss, younger women and Swiss older men, for example), this can lead to fault lines between groups, with the danger that companies cannot reap the benefits of diversity. So this needs to be carefully managed to avoid conflicts (Lau & Murnighan, 1998; Jackson & Joshi, 2011).

60% of all promotions in the MEM industry go to employees aged 31 to 40, which is higher than the average of all industries. However, among lowest and lower management promotions in this age group, women only have a share of 23%. That percentage is lower than their share among lowest and lower management promotions across all age groups. Interestingly, women between 31 and 40 are heavily represented among new hires in lowest and lower management, where their share is 37%.

Regarding middle and top management, the difference between promotions and new hires is particularly stark between 41 and 50 (when most career moves into these positions occur). 13% of promoted employees in this group are women, compared to 23% of hires. Women are more likely to be externally recruited into middle and top management positions than promoted internally.

The MEM industry has a solid full-time culture, reflecting a certain lack of flexibility. Employment percentages are among the highest in any industry, particularly in non-management. Full-time is not only necessary to attain a management position but seems to be the norm throughout.

It is important to note that the average employment rate for women between 31 and 40 in lowest and lower management is higher than for other industries, i.e., men’s and women’s employment rates are closer. Full-time work seems to be expected, which may pose challenges for employees – but at the same time explain why women rise to the top at higher rates than in other industries. In the MEM industry, the part-time penalty simply doesn’t apply!

But this also means that diverse employees with diverse needs may not be attracted to the MEM industry and instead choose to work in different sectors. So, while some types of flexible work may not work that well in the MEM industry, it may be time to come up with creative solutions.

Rethinking leadership: MEM companies should re-evaluate job requirements to determine which criteria are truly necessary and which are nice to have to become a leader – thus broadening their pool of potential new hires for managerial positions. For instance:

Identify and develop diverse role models – and ensure they are visible: One effective measure is to make women in STEM professions more visible at the industry level, within and outside the company (Roemer et al., 2020). In doing so, it is important to identify and strategically engage authentic, female role models. But how can you identify these female role models and make them visible?