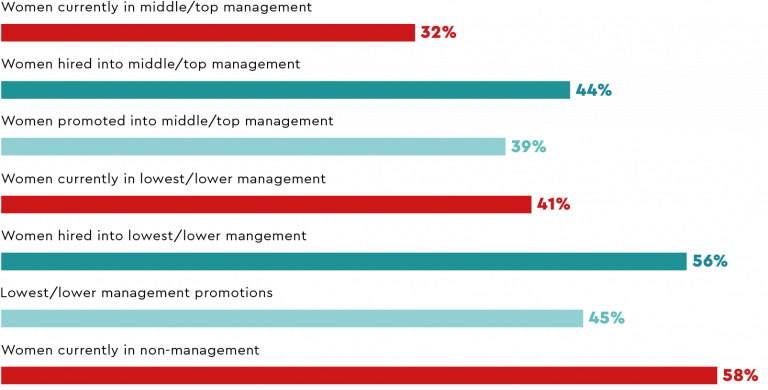

Compared to all other industries, the Public sector has the highest share of women at every management level (as well as non-management). However, the percentage of women in top management for the Public sector is less than half of the percentage in non-management. Women are currently considerably underrepresented above the lower management.5

5 Because several of the Public sector organizations do not differentiate between lowest and lower management in their HR data, these two levels were combined in this chapter.

One possible explanation is the combination of age and tenure time for those in top leadership positions. Over 60% of middle and top management men are over 50 years old, and more than 16% are over 60. These numbers are considerably higher than the average of all industries. The average tenures in leadership positions are also considerably longer, particularly for men. This length of tenure indicates that key leadership positions simply do not open up, representing a blockage in the talent pipeline. This presents a great opportunity, too. As these male leaders are going to retire soon, positions can be filled with diverse candidates (who champion inclusion).

On the other hand, the most significant drop in women’s representation happens between non-management and lowest or lower management, which means that women are already less likely to advance before the “blockage” in middle and top management.

Compared to the share of 58% in non-management, a share of 45% for women in promotions to lowest/lower management is low, though it slightly raises the percentage of women in springboard positions. The typical employee making a move into management in the Public sector is Swiss, male, between the ages of 31 and 40, and has a tertiary degree.

Conversely, women are more strongly represented in new hires into management.

The largest percentage of all management promotions is awarded to employees between 31 and 40 years old. In this age bracket, men are more than twice as likely to be promoted. Interestingly, the share of women and men promoted past the age of 40 is very balanced.

Regarding middle and top management, both internal development and external recruitment contribute to increasing the share of women.

So, why do lowest and lower management promotions stand out rather negatively?

These promotions fall squarely into the “family prime time,” when women in springboard positions (lowest and lower management) as well as non-management reduce their employment percentages considerably, while men’s stay the same. The difference in employment percentage by gender around “family prime time” is particularly pronounced in the Public sector. Though family-friendly, life-cycle-oriented working models are attractive for diverse employees and especially those with care responsibilities, they can have a negative impact if part-time work is an obstacle to career progression – from a gender diversity perspective it is especially challenging if it is primarily women who work part-time.

Particularly striking: While only 45% of employees work full-time, 60% of all promotions go to full-time employees (though the disadvantage only occurs once employees work below 80%). Traditional conceptions of work and parenthood prevent women from advancing internally in the Public sector, more so than in other industries.

As 16% of male middle and top managers in the Public sector are over 60 years old, the time to plan what future leadership will look like (in terms of diversity and inclusion skills) is now. This planning is crucial as certain part-time penalties and a traditional conception of career seem to prevail. What can Public sector organizations do?